Show Notes

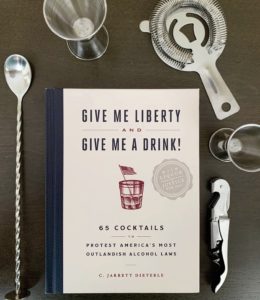

Jarrett Dieterle is a resident senior fellow studying alcohol policy at the R Street Institute, a think tank in Washington, D.C. His book, Give me Liberty and Give me a Drink, was published on September 15, 2020. It details the ironic, comical, and often extraneous booze-related laws enforced in the United States. Dieterle humorously assigns an inspired cocktail to each regulation, bringing an air of comedy to his writing as well as a clever way to expose the idiocies of these policies. His goal, as he states, is to give people bite-sized access to a wealth of information on the topic of alcohol policy which they may have previously taken for granted. He emphasizes that these idiosyncrasies are not bound to one state; they expand over the entirety of our country, rooted in Colonial times.

The one thing Dieterle hopes a reader will take away from Give me Liberty and Give me a Drink is that they begin to question their surroundings. Give me Liberty and Give me a Drink takes something which functions in the background of awareness and systematizes it, transforming it into a cohesive existence which prompts the question of why? Why do these laws exist? Why do we need them?

The age-old dichotomy between freedom and security is often brought up in the argument of alcohol regulation. The negative externalities are obvious. Jarrett is not trying to deny that drunk driving, alcohol abuse, and illicit alcohol are issues that need government supervision. However, it becomes nonsensical when we focus on Prohibition-era laws which have prevailed past the 21st century. For example, the Massachusetts “Blue Laws,” which prevent the purchase of alcohol on Sundays and require businesses to pay compensation if they wish to continue sales. There is no discernable pattern in their data that the Blue Laws have impacted drunk driving, and yet the regulations stay in place.

Some other rather infamous laws include:

The Indiana Warm Beer Laws: grocery stores/gas stations are only allowed to sell beer if it is at room temperature. However, the liquor store can sell it cold creating a monopoly within the beer industry.

Utah’s Zion Curtain: There must be a partition barrier in-between the bartender and the individuals buying alcohol, leading us to the question: what convincing argument keeps this law instated?

Washington State: distilleries can only serve up to two ounces of their spirits per day. This limits their ability to create a good impression on their customers and prosper through word of mouth.

Virginia: Distillers can only sell in Virginia ABC stores. If the ABC accepts none of the distiller’s products they are locked out of the marketplace.

Do you have questions for Jarrett Dieterle? Contact him here.

Interstate shipment links:

Where Retailers Can Ship DtC

Direct-To-Consumer Shipping Laws for Wineries

DTC Shipping 101: A survival guide for the beverage alcohol industry

Direct Shipment of Alcohol State Statutes