Preface

This essay, at its core, is an investigation about differences between generations and how the current up-and-coming generation can do a better job as stewards of the spirits and cocktail landscape. It has to do with understanding what you personally value in a drink and how you choose communicate that to other people as we all strive to all be part of the tide that raises all ships.

That said, we hope you enjoy this essay by CEO Eric Kozlik about why he thinks the word “smooth” needs to go away. Please enjoy.

Scotch & Cribbage

I was sharing a drink with my dad recently over the holidays. If you’re curious about the specifics, we were comparing Balvenie Double Wood (a Scotch finished for 9 months in Oloroso sherry casks) and Monkey Shoulder, which is a blend of Single Malt whiskies. Both really interesting.

I commented that I wasn’t keen on the heavy sherry notes on the Balvenie. Personally, I’m more interested in the flavors that come from the base grain and the fermentation than the notes of the barrels that the whisky was aged in. And my dad’s response was,

“Oh don’t get me wrong, I love Monkey Shoulder. But this Balvenie is just so SMOOTH.”

That’s it. We enjoyed our drinks. We played a few games of cribbage, which is our father-son activity where we can bullshit and catch up with one another – and then I went home. But since then, I’ve been really thinking a lot about this word “smooth.”

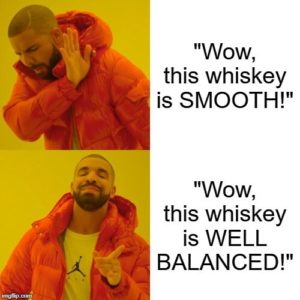

To me, “smooth” is uninteresting. A smooth landscape is just a flat plane with no topography or defining features. Smooth is boring. It’s the absence of a feature, somehow communicated as a good thing. Smooth is comfort derived from homogeneity, a welcome blandness that lulls you – or some part of you – to sleep.

But clearly to my dad, and to other folks like him, smooth is a good thing. To him, smoothness indicates craftsmanship – that ability to take a set of raw materials and finesse all the roughness out of them. To him, smooth is stepping into a shower or a pool that’s just the right temperature, as if the world somehow anticipated your desires and adjusted itself to meet them.

When my dad tells stories about his college days – where he first started drinking booze, he references playing endless hands of – you guessed it – cribbage while drinking Cutty Sark blended Scotch. Now, before I proceed to throw Cutty Sark under the bus here, I want to put in the disclaimer that I’m not a snob. I value all sorts of spirits at all sorts of price points. But the fact of the matter is: Cutty Sark is a lower-middle-shelf blended scotch whisky. It’s fine, but it’s nothing to write home about.

I can’t say for sure how Cutty Sark tasted in the 70s when my dad first drank it – but even taking today’s product as our frame of reference, it has a few harsh, somewhat unrefined flavor notes that come from making a low cost commodity whisky at massive scale. So when you put it in context, it makes sense why my dad might place “smooth” whisky on a pedestal. It’s a step up from humble beginnings, which means that “smoothness” must be associated with higher quality products.

Swamp Rats & Moonshine

Pop culture also seems to bear this out. Just look at that popular cartoon trope from the mid-20th century where some character takes a swig from a jug with three “X”s on it and then breathes fire or at the very least, sputters and makes some unpleasant faces. In the show notes page for this episode, I’ll put a couple video links to this type of scene, sourced from the 1977 Disney movie, The Rescuers. In the film, a couple city mice end up in the bayou, where they encounter some of the local swamp animals, including a rat with a big ol’ jug of moonshine in tow. At one point, the liquor is used to revive a dragonfly in the same manner that you’d use smelling salts or a defibrillator to jolt someone back into the world of the living.

Basically what’s implied here is, there’s two types of spirits in the world: the kind that make you breathe fire, and the kind that don’t. And I suppose, on the face of things, I can’t really disagree with that. But it does seems just a bit too simple, doesn’t it?

Spirits as Commodities in the 20th Century

One way to throw a little more light on the situation might be to stick with the historical or generational take on the spirits world for just a bit longer and ask the question: why was this binary smooth vs. rough spirits stereotype so prevalent in the mid-20th century that it continues to influence our preferences and word choice decades and decades later?

I think some of it has to do with the way our culture (and other cultures around the world) recovered from two world wars and (at least here in the U.S.) Prohibition. During the 20th century, almost everything we consumed here in the United States became commodified, and when something turns into a commodity, meaning that it’s almost universally available and inexpensive enough for mass consumption, there are some definite pros and cons.

Commodities are great if you don’t have a lot of money or if you don’t have the time or resources to make or source a given item yourself. But if you’re looking for quality or a particular unique character in the product you intend to consume, commodities are terrible.

So in the second half of the 20th century what you saw in the international spirits market was the rise of brands that had enough manufacturing power to produce affordable spirits, smart enough technicians and executives to settle on formulas that tasted decent despite being made at massive scale, and marketing departments that could tell a compelling enough story to get consumers on board.

During this time, the word “smooth” came into play when you could hold a bottle in your hand that had the price tag of a cheap commodity, but the flavor profile of something a little bit better. I mean, come on, everybody likes a deal, and that, I believe, is the little dopamine rush that reinforced our cultural penchant for somewhat bland spirits that were just tasty enough to avoid being labeled commodities.

Plus, during that same time frame, people also gravitated toward spirits that were supposed to be flavorless, like vodka. And we were dumping so much sugar and juice into our cocktails that it really didn’t matter too much what the spirits tasted like. Fast forward to today, and we’re relieved that great, nuanced cocktails are back on the menu, but that pesky, reductive word, “smooth” is still hanging around, like your great aunt who still thinks she’s living in the 70s.